History

Welcome to Historic Fort Wayne

The site of Historic Fort Wayne has a history deeply entangled with Detroit and the surrounding communities. Its significance predates military use, as it served as an important trading and gathering point for Native American groups for millennia. Over the past thousand years, this area has been a Potawatomi village and sacred burial ground, a colonial trading site, a diplomatic meeting ground, a station on the Underground Railroad, an important military logistics center, and a home to troops and civilians alike. Now, it is a park nestled along the Detroit River and an important historical and cultural heritage site.

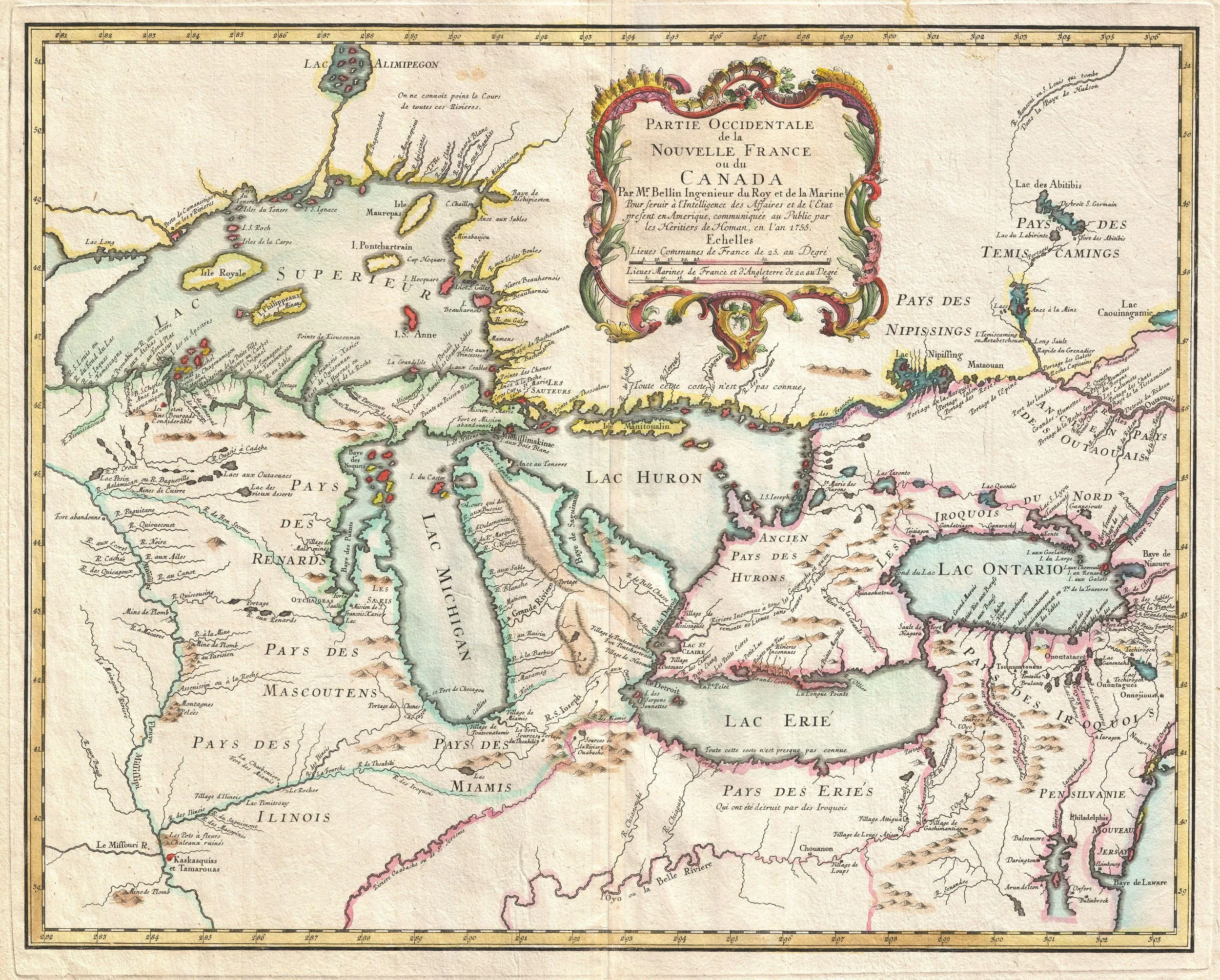

Echoes of Early Detroit

Detroit’s first military installations, Fort Pontchartrain du Detroit (1710-1796), built during French occupation, and Fort Lernoult, built during British occupation, stood in what is now downtown Detroit from 1779-1826. Their locations were chosen strategically to overlook the narrowest point of the river, and besides military use, forts also served as centers of commerce and trade. Fort Wayne, located three miles to the south, was first constructed by the US military fifteen years later in anticipation of American-Canadian conflict. The original limestone “star fort” built in 1845 still remains, as do the original 1848 barracks.

A Witness to National Transformation

Fort Wayne experienced a sleepy first few decades of existence, as the potential of conflict with Canada lessened as concerns of further rebellions forced the Americans and the British into a tenuous alliance. It was not until the 1860s, with the outbreak of the Civil War, that the fort was used for formal military training for Union troops. Though no armed conflict has ever taken place at this site, Historic Fort Wayne also played a key role as part of the region’s Arsenal of Democracy, providing manufacturing and logistical support of allied efforts in the two World Wars.

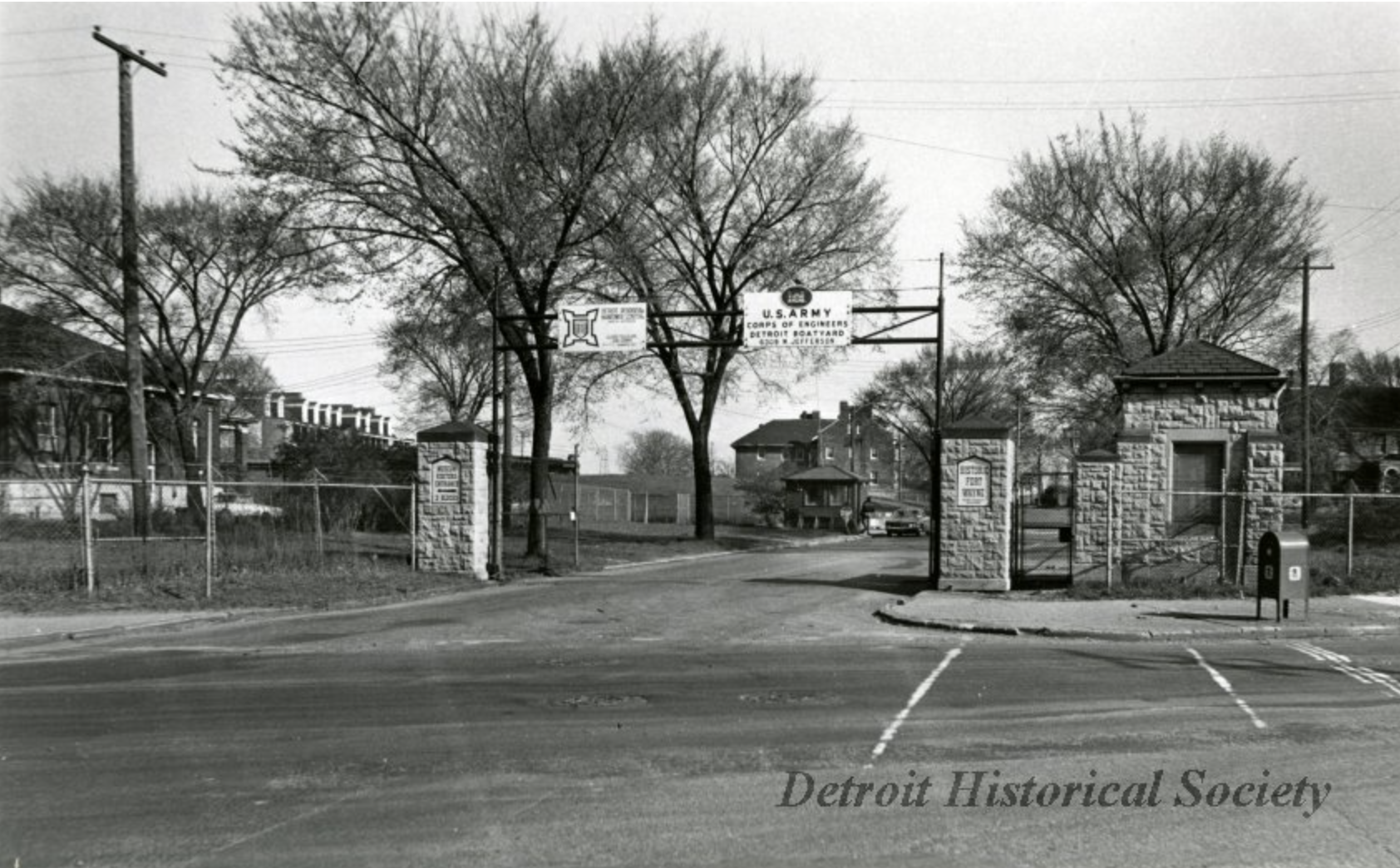

Historic Fort Wayne Today

As the city gradually took ownership of the entirety of the site, it was a place of refuge, serving as housing for displaced Detroiters from the Great Depression to the conflicts of 1967. For many living veterans, the fort evokes memories of induction during the 1960s and 70s, when the national draft was implemented for the Vietnam War and new draftees were processed here. The City of Detroit now owns and operates most of the site, while the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers maintains offices and a boatyard along the river. The Fort was designated a Michigan State Historic Site in 1958 and listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1971.

Today, the former active military site has been transformed into a public park with community soccer fields, scenic picnic grounds, and historic event spaces. Historic Fort Wayne is open to the public, and welcomes curious Detroiters and visitors alike to explore its layered past. Explore other areas of Historic Fort Wayne’s history below.

A Sacred Place: Native American Heritage and Contemporary Life

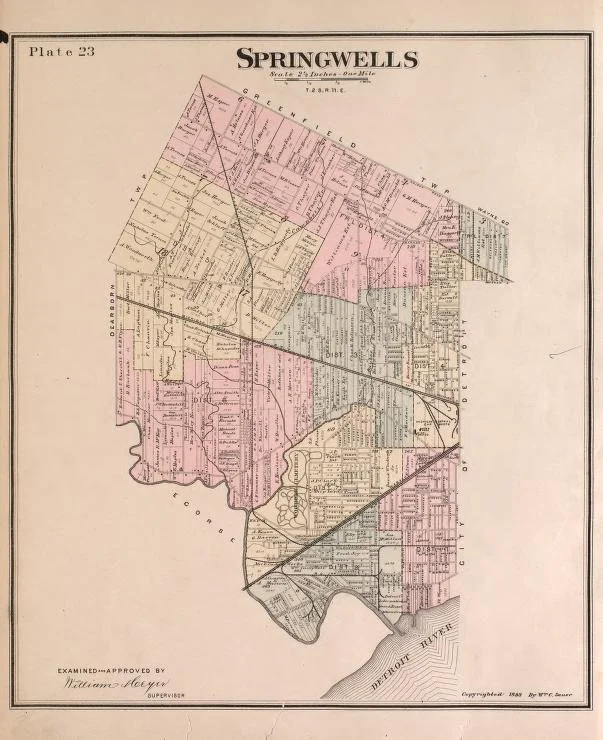

Dating from ~AD 750 to 1200, the Fort Wayne Burial Mound was once part of a larger Native American burial complex in the Detroit region known as the Springwells Mound Group. This group consisted of at least five or six known mounds that were located within a mile’s radius of the current location of Historic Fort Wayne. The Fort Wayne Mound is the last remaining burial mound of the Springwells Mound Group.

As late as the early 1800s, numerous Native Americans living in the Detroit area were known to have buried their ancestors in the mounds at Fort Wayne and other surrounding mounds. Today, the Fort Wayne Mound is a sacred place to the descendants of these Native American ancestors. The City of Detroit is working with the Nottawaseppi Band of Huron Potawatomi to identify future options for stewardship. Contemporary tribal nations, like NHBP, are descended from the “mound builders” and have strong spiritual connections to this place. Read more about NHBP’s work to reclaim ancestors here.

The Fort Wayne Burial Mound in 2023. (Nottawaseppi Band of Huron Potawatomi).

Map showing the future site of Historic Fort Wayne in the mid-1840s. On the west side of the Detroit River. (Chart Of Detroit River, From Lake Erie To Lake St. Clair. Surveyed In 1840, '41, & '42, By Lts. J.N. Macomb And W.H. Warner; Under The Direction Of Captain W.G. Williams, Rumsey Map Collection).

This map shows the township of Springwells in 1891, including Historic Fort Wayne. (Library of Congress).

Sustaining Life: Springwells and the Detroit River

Hundreds of years ago, the area we now call Wayne County consisted nearly entirely of marshlands, dotted with beaver dams and teeming with flora and fauna. The river served as a significant gathering spot for Indigenous communities, including the Anishinaabe, the Wyandot (Wendat), Fox (Meskwaki), and the Miami (Myaamia) peoples. Anishinaabe people called the region “Waawiyaataanong,” roughly meaning “at the curved shores,” to reference the shape of the shoreline.

French colonists later named the area le détroit du Lac Érié, meaning “the strait of Lake Erie.” The river thus was often called Rivière du Détroit, meaning “river of the straits.” Over time, this shifted into the name we know today, Detroit. The area we know as Historic Fort Wayne was once called Belle Fontaine, or Springwells, named after the naturally flowing freshwater springs and spring-fed creeks that once dotted the landscape.

Early European settlers described the area as having sandy bluffs overlooking the river’s bends, forests lush with life, meadows sparkling with wildflowers, and wetlands teeming with wild rice beds. As Detroit expanded, the landscape shifted.

French colonists developed a unique agricultural system reliant on the riverbank that set the groundwork for Detroit today. Ribbon farms are a type of agriculture where the plots are long and narrow, giving each farmer access to the river. Several creeks and rivers feed into the Detroit River, allowing farms to be built to facilitate irrigation, travel, and trade. Fronting on the Detroit River and very close to Fort Detroit, strip farms were well positioned to sell their harvest to the garrison and fur trader operations based in Detroit.

Border Stories

European settlement turned what was once simply a river into an international border. This created a sprawling transnational community that frequently crossed the river to work, visit with family, attend church, go to school, and shop. Detroiters of all backgrounds had extended networks spanning the region similarly to the watershed itself.

The border between the United States and Canada at the Detroit River was porous in the mid-1800s, meaning people crossed frequently for many reasons. This made it easier to help people fleeing slavery because frequent border crossings were common, and thus communities organized themselves to assist in anti-slavery efforts. Detroit-based abolitionist organizations that assisted in escape efforts across the river and organized education and social assistance programs. Members of these organizations often worked together to provide aid at great personal risk to their lives and livelihoods, when the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 criminalized their work.

Samuel Zug was an abolitionist and merchant that lived just south of Historic Fort Wayne, on what is now Zug Island. Zug was a key member of the Michigan Anti-Slavery Society, and likely assisted escaping slaves in crossing the Detroit River. Zug also owned land in Essex County, Ontario. Zug’s property holdings and his sympathy and support for escaping slaves suggest frequent cross-border activity.

Research on Historic Fort Wayne’s role in the Underground Railroad is ongoing.

Etching of the southeast corner of Fort Wayne and Dock, Detroit, Mich., August 31st, 1884. Canada’s shoreline is visible in the background. (Detroit Historical Society).

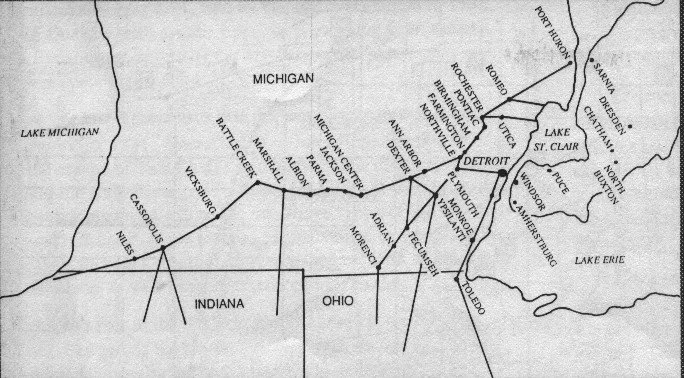

Map showing known Underground Railroad stops in Michigan. (Shelby Township Historical Committee).

Home at Historic Fort Wayne

Though being unique as a military installation that never experienced battle, Historic Fort Wayne has served a multitude of uses throughout its history. The fort has served as temporary housing more than once. During the economic downturn of the Great Depression, Civilian Conservation Corp (CCC) workers were housed on site. The CCC, a New Deal program, provided employment to young, unmarried men, along with civic and political education. Fort Wayne also benefited from the Works Progress Administration, and many improvements were seen. Recreational activities increased during this time as more people lived on site.

Families affected by unemployment and homelessness during the Great Depression lived in temporary housing set up in the Barracks. Later, the long, hot summer of 1967, and resulting rebellions and riots, displaced many Detroiters. Several buildings were leased to the Detroit Housing Commission beginning in 1967 and housed displaced families for several years.

Beckoning to its history of automobile manufacturing, in the late 1980s, the fort hosted numerous car shows, including the Spirit of Detroit Car Show and Swap Meet. This event was attended by thousands of people, and showcased vintage and new cars in celebration of Detroit’s history and craftsmanship.

Detroit public welfare housing at Fort Wayne in July 1948. (Detroit News Archives).

WPA artist Joe Sparks paints soldiers on mural at Fort Wayne in Detroit in 1938. (Detroit News Archive).

A Story of Stewardship

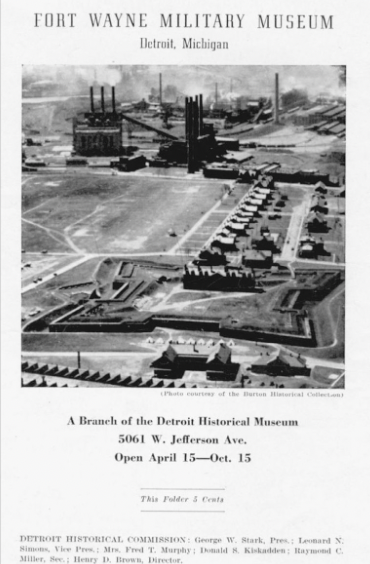

Historic Fort Wayne was once home to three museums on site: the Fort Wayne Military Museum, the Tuskegee Airmen Museum, and the Great Lakes Indian Museum.

The United States’ first Tuskegee Airmen Museum was built at Historic Fort Wayne in 1989. The museum honors the Tuskegee Airmen, the first black military airmen in America - Mayor of Detroit Coleman A Young was a Tuskegee Airman. The museum collections are now displayed at the Coleman A. Young International Airport.

Opening of the National Museum of the Tuskegee Airmen, 1989. (Detroit News Archive).

A brochure for the Fort Wayne Military Museum. (Detroit Historical Society).